History of Ballet

Positioned by Fashion by Adrian Clarke

Ballet and the Renaissance Man by Adrian Clarke

Tights Connection to the Beginning of Ballet:n by Adrian Clarke

by Adrian Clarke, L.O.C.A.D. – Library of Costume and Design

Masks have been there from the beginning with Ballet, giving us such spectacular displays as the masquerade ball scene from, “Cinderella”. The use of masks evokes the notion of intrigue and mystery for it enabled ‘Romeo’ to meet his ‘Juliet’, the famed star crossed lovers to meet at that fated masked ball. They also help in the portrayal of transformation like for ‘Bottoms’ in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” when he was turned into a donkey

Masks have been there from the beginning with Ballet, giving us such spectacular displays as the masquerade ball scene from, “Cinderella”. The use of masks evokes the notion of intrigue and mystery for it enabled ‘Romeo’ to meet his ‘Juliet’, the famed star crossed lovers to meet at that fated masked ball. They also help in the portrayal of transformation like for ‘Bottoms’ in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” when he was turned into a donkey

The use of masks isn’t particularly unique to Ballet or to Western European Theatre for that matter. Masks are used in a myriad of ways in many cultural traditions around the world. What is unique with Ballet, is how masks were first used as an obligation and from which, what would emerge.

The obligation of wearing masks in the early ballets was inherited directly from the ‘Commedia dell’Arte’ at the French Court. However, even for the Commedia it was essentially an extension from a peculiar notion of ‘Egalitarianism’ that developed during the European Renaissance. It was believed through Anonymity one could experience freedom from the pressures of society’s expectations. This is pertinent as many of these ballets were performed by royalty, nobility and commoners alike. Together, they created dance spectacles rich in symbolism relevant to the culture of the day. From behind the mask, the many actors and dancers were afforded a freedom to assume any character from any class in society or a personification of a deity without any fear of consequence or reprimand.

To understand the reason behind the use of masks in these ballets is like to understand the layers of an onion. It was complex and subtle but in saying that, their purpose was essentially twofold. The first was as for the Commedia, they helped to give an idea of the character’s role. These are purported to have developed from the masks of the obscure ancient Roman ‘Atellan Farce’, a form of comic theatre that began around the third century before Christ. The masks of the Commedia developed over the generations of actors with them grew certain traditions that held steadfast. All the characters had their own recognisable masks and costumes, stock gestures and stage business which could be relied upon to guarantee to create a laugh and put the audience in tune for the entertainment to follow. Thus, in the course of time these were crystallised in each mask an entire code or vocabulary of repertory phrases that were appropriate for the role which could be memorised and made to fill in the blanks when the actor’s wit fails. It was primarily the male characters that wore the masks, each representing an aspect of Italian life as well as the political and economic landscape of the European Renaissance. Such roles required actors to make a serious study of their parts, and take pride in their achievements. They were willing to accept the discipline which all professional Arts demands. These comedians changed forever the standards of acting with the most gifted of them making the role completely their own.

For the early Ballets such as “The Queen’s Comic Dance” their designs would take on a similar semblance as those used in the Commedia, however, drawing upon more potent symbolism taken directly from the Classical Mythology of the ancient Romans and Greeks. They were further endowed with pertinent political, religious and social references to give them a more contemporary relevance for the intended audiences namely the ruling classes of France. After all Catherine de Médicis had Ballet created to be a propaganda machine.

The second, however, was from a far more abstract notion as embraced from the ancient Venetian Republic. It came from a peculiar custom concerning public festivities like the famed ‘Carnevale Maschere’ (Masked Carnival) of Venice. The Republic of Venice would have it that all participants at such public events were expected to wear masks. It was reasoned just by wearing masks, the barriers of class distinction that otherwise prevailed were suspended. This notion for the Venetians was not a new one or any way unusual as masks were an important element of the social and political landscape of their most serene republic since ancient times. The male members of the Patricians, the Venetian ruling class, were the only ones who had the right to participate in any election to any political office when made vacant. The electoral process was always by a secret ballot which was always conducted anonymously behind white masks called ‘Bautas’ and under black cloaks. Furthermore, it was by the then Venetian law that no retribution could be exacted against anyone who wore a mask. This was a useful point of law for the actors of the Commedia when they drew the ire of the authorities in Venice.

Masks were also useful for these actors elsewhere in Italy and abroad as they could never be recognised when they had to lose themselves in the crowds when the humour of their satire was to prove too cutting for the authorities to appreciate with soldiers sent to crash the performance. During such occasions it paid not to stand out. The again the spectacle of the lively cat and mouse between the actors and soldiers was often much to the delight and enjoyment of the crowds. This is perhaps what the young Catherine de Médicis also enjoyed watching from the balcony or window all those years before?

At the French Court, this customary practice of the mask was readily extrapolated into Ballet. For Catherine and other members of the Royal Family, it helped with the perplexing problem of how to mitigate the issues of social convention arising from the strict protocols regarding rank and file. The conundrum was as many professional performers were from the lower classes that had been afforded patronage from wealthy benefactors. This mingling of the classes was achieved with the aid of the mask which enabled any dancer who could have been an offspring of a cheese-maker to dance alongside the King and Queen of France. When otherwise it would unlikely such an individual by polite means would have been able to be seen inside the palace gates let alone the great halls. Did this, however, gave rise to the dangerous idea of Human Equality in the face of Absolute Monarchy? One can only speculate.

Furthermore, during the mid-16th Century, the idea of public anonymity would carry over into the many ‘Masques’ (masked balls) which were often open to those who were able to afford to attend which did include many ballets performed as part of these public events. This idea of egalitarianism would also manifest in ways that were often rich fodder for the wagging tongues of gossip mongers with the idea of ‘Dangeous Liaisons’ fomenting behind the fluttering of fans and the swish of a cape.

The many masks for the early ballets would evolve from the masks of the Carnevale imported from Venice and other Italian cities. For the Carnevale there were essentially a handful of designs that developed during the 17th and 18th Centuries. All of which have become very much associated with the famed festival. Each design is known by its own name and comes with rules of its use that has become entrenched in tradition. Each design would arise from particular episodes in history, from the Venetian political landscape, or new social trends that would embody the collective memory associated with such events. Some masks were engendered and class oriented in its use like as for the ‘Bauta’, which over time would later become worn by both genders and by those who were more of the upper middle classes. The ‘Bauta’, is a white mask that covers most of the face with it only allowing the chin to be free of any restriction, thus the wearer was able to speak. By then the custom was it to be worn with a short hooded black cape and tricorn hat as pictured, fig. 02.

The many masks for the early ballets would evolve from the masks of the Carnevale imported from Venice and other Italian cities. For the Carnevale there were essentially a handful of designs that developed during the 17th and 18th Centuries. All of which have become very much associated with the famed festival. Each design is known by its own name and comes with rules of its use that has become entrenched in tradition. Each design would arise from particular episodes in history, from the Venetian political landscape, or new social trends that would embody the collective memory associated with such events. Some masks were engendered and class oriented in its use like as for the ‘Bauta’, which over time would later become worn by both genders and by those who were more of the upper middle classes. The ‘Bauta’, is a white mask that covers most of the face with it only allowing the chin to be free of any restriction, thus the wearer was able to speak. By then the custom was it to be worn with a short hooded black cape and tricorn hat as pictured, fig. 02.

Others that would develop, include the ‘Moretta’ (Dark Lady) or ‘La Servetta Muta’ (The Mute Female Servant) which is a simple round black mask that barely covers the face of the wearer which was obviously a woman. It appears that it developed from the ‘Visard’ mask that was used by travelling ladies to help protect their skin from sunburn. In Venice, these were associated with a particular class of noblewomen. It would eventually lose favour with it nowadays appearing mainly as a novelty rather than a traditional design. This is due to the awkward manner of its use. It is held in place by a mouth bit, which explains why it has no mouth opening.

Others that would develop, include the ‘Moretta’ (Dark Lady) or ‘La Servetta Muta’ (The Mute Female Servant) which is a simple round black mask that barely covers the face of the wearer which was obviously a woman. It appears that it developed from the ‘Visard’ mask that was used by travelling ladies to help protect their skin from sunburn. In Venice, these were associated with a particular class of noblewomen. It would eventually lose favour with it nowadays appearing mainly as a novelty rather than a traditional design. This is due to the awkward manner of its use. It is held in place by a mouth bit, which explains why it has no mouth opening.

The ‘Medico della Peste’ (Plague Doctor), with its long beak protruding developed as a result of the ‘Black Plague’, thus emulating the protective masks as worn by the doctors treating the many victims. Despite its ominous appearance, the Commedia and revellers of Carnevale were able to find some sense of humorous irony in the midst of tragedy arising from one of the darkest episodes of European history.

The ‘Volto’, a full-faced mask encompassing the chin, the cheeks and forehead comes complete with eye holes. It is the most popular of the masks across the spectrum of Venetian society, it is also known as the “Citizen Mask”. The design is of a simple, somewhat stoic expression complete with nose and closed lips. By tradition, it is a plain alabaster white mask which has earned it the name of ‘Larva’, Latin for ‘Ghost’. Worn with a black tricorn and a full length cape covering the whole body of the wearer, thus whoever was to greet the wearer would basically see a white face appearing before them as if without a body in the dim light of twilight. Such similarly costumed figures appear in Cranko’s ballet, “The Taming of the Shrew” as lantern bearers. Nowadays, the ‘Volto’ mask is often colourful with two or three colours on one mask embellished gold detailing of florid motifs complete with beads, and crystals sometimes topped with a splay of feathers, flowers or fabric to be complemented by an equally elaborate costume of rich and lavish design.

The ‘Volto’, a full-faced mask encompassing the chin, the cheeks and forehead comes complete with eye holes. It is the most popular of the masks across the spectrum of Venetian society, it is also known as the “Citizen Mask”. The design is of a simple, somewhat stoic expression complete with nose and closed lips. By tradition, it is a plain alabaster white mask which has earned it the name of ‘Larva’, Latin for ‘Ghost’. Worn with a black tricorn and a full length cape covering the whole body of the wearer, thus whoever was to greet the wearer would basically see a white face appearing before them as if without a body in the dim light of twilight. Such similarly costumed figures appear in Cranko’s ballet, “The Taming of the Shrew” as lantern bearers. Nowadays, the ‘Volto’ mask is often colourful with two or three colours on one mask embellished gold detailing of florid motifs complete with beads, and crystals sometimes topped with a splay of feathers, flowers or fabric to be complemented by an equally elaborate costume of rich and lavish design.

There are other mask styles, with most of which have been borrowed directly from the ‘Commedia’. The two main variations of these are known as ‘Pante’ as from the character ‘Pantalone’, one who wears pants, and ‘Zanni’ both furnished with their own version of a long beak nose.

All of these masks would appear in ballets at one time or another along with those specially created for these ballets. Today, the idea of wearing masks is so alien and for some designs they appear downright scary. This however is irrelevant to us as for those in the 17th and 18th Centuries they were imbued with elements of social and political potency.

The original masks of the Commedia and Carnevale were made from various materials. Wood with cypress being the most favoured, copper or brass, and liken to those of Greek and Roman antiquity. Later, porcelain, and even glass were used which the Venetians been long since famous for the production of. Even papier-mâché was used in order to keep with increasing demands for masks. However, most convenient for Ballet, leather had become the most preferred used material in the production of masks. These started originally as simple, natural leather or plain all black or white designs. Over time the masks would become entrenched in their respective traditions with those for the Commedia with its stock characters, then those for Carnevale would acquire more decorative embellishments thus becoming the familiar elaborate creations that it is known for often complete with gold gilt detailing. Regardless of this diversion between the two, Ballet was to draw from the two traditions well into the 20th Century.

During the height of the popularity of Carnevale, mask makers were to enjoy the respect born out of public reverence that would have them enjoy a special legal status within Venetian society. With this they established a guild that issued strict rules in regards to the manufacture of masks and for those apprenticed to the craft. They would become regarded as ‘Artisans’ as opposed to ‘Tradesmen’ thus rising to a level of respect and celebrity that was originally once reserved for famed artists of the stage, literature and painting. With to the steady flow of exchange in artists between Italy and France, many of these artisans would make their way to the French Court where many of their masks would find their way into Ballet.

What is interesting, during the late 17th Century in France with the rise of the ‘Comédie-Française’, a new mask design of a simple black half- face mask would come to the fore and is very much used in many ballets today. It is what is called a “Soubrette”, meaning “Coy” in French, or “Pierette” as it was worn by the named female character being one of the French personifications of ‘Columbina’, which by the way is the other name for the mask. This style of mask was particularly made famous by the French actress of the Comédie, Mademoiselle Clarion. Its origin is debated with many assert that it is Italian, when many say it is French due to its association with that of Clarion, when others assert it is purely a 19th Century creation born out of the popular theatre of the pantomimes and harlequinades. The third assertion does fall flat as there are several lithographs and paintings from the late 17th and 18th Centuries depicting female actors of the Commedia and Comédie-Française along with those of revellers at Carnevale wearing such masks. This confusion can be forgiven as by the 19th Century it was worn by both men and women alike in the popular stage shows of the Music Halls. It is also a recognisable feature of the costumes worn by the ‘Harlequin’ and ‘Columbine’ dolls from “The Nutcracker”. Nowadays, this style is made from a myriad of textiles including rubber. Sometimes there is a subtle distinction between the intended genders by the eye holes being more rounded for the female version. It can be plain in black or trimmed in gold or silver or completely gilded embellished with beads, crystals and sequins often topped with feathers of various types. Either it is secured to the face by ties or a strap or is held as fastened to a short stick to be used as a handle by the wearer.

What is interesting, during the late 17th Century in France with the rise of the ‘Comédie-Française’, a new mask design of a simple black half- face mask would come to the fore and is very much used in many ballets today. It is what is called a “Soubrette”, meaning “Coy” in French, or “Pierette” as it was worn by the named female character being one of the French personifications of ‘Columbina’, which by the way is the other name for the mask. This style of mask was particularly made famous by the French actress of the Comédie, Mademoiselle Clarion. Its origin is debated with many assert that it is Italian, when many say it is French due to its association with that of Clarion, when others assert it is purely a 19th Century creation born out of the popular theatre of the pantomimes and harlequinades. The third assertion does fall flat as there are several lithographs and paintings from the late 17th and 18th Centuries depicting female actors of the Commedia and Comédie-Française along with those of revellers at Carnevale wearing such masks. This confusion can be forgiven as by the 19th Century it was worn by both men and women alike in the popular stage shows of the Music Halls. It is also a recognisable feature of the costumes worn by the ‘Harlequin’ and ‘Columbine’ dolls from “The Nutcracker”. Nowadays, this style is made from a myriad of textiles including rubber. Sometimes there is a subtle distinction between the intended genders by the eye holes being more rounded for the female version. It can be plain in black or trimmed in gold or silver or completely gilded embellished with beads, crystals and sequins often topped with feathers of various types. Either it is secured to the face by ties or a strap or is held as fastened to a short stick to be used as a handle by the wearer.

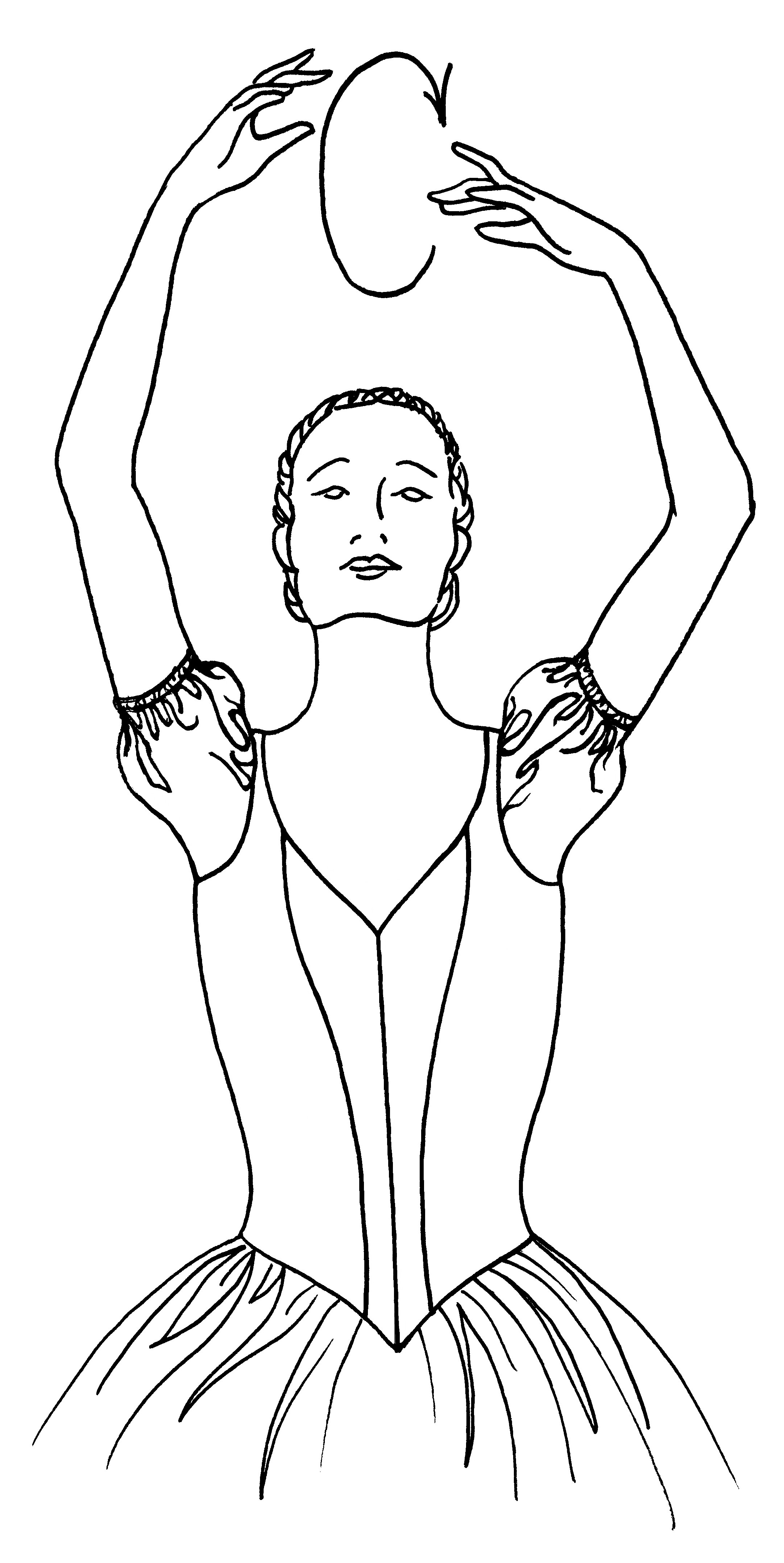

Most importantly the masks for Ballet came with a gift, one of the ‘Language of Gestures’ that we know today as ‘Mime’. It is one of the most unique gifts that the Commedia gave not only to Ballet but to Theatre as a whole. From the established custom of wearing masks, Mime has prevailed upon Ballet since following that famed night with the performance of the “Queen’s Comic Dance” in 1581. With each new era adding a new nuance to the language, the vocabulary would develop and evolve over the generations of dancers.

Initially it was used within the Commedia as an extension, a visual flourish to help reinforce what was being said by the comic actors. Slowly, over time, the gestures were refined as such that their meaning was clear in the action and thus required little or no added verbal explanation. With the early ballets, this did prove useful with it only helped along with use of poetic prose and the ambience of music, thus allowed those performing to focus on the technique of dance and mime without the added burden of trying to be heard over the music.

Many gestures would develop in a variety ways with some to become associated with a particular form of theatre or social forum. The latter is particularly the case with some of those incorporated into Ballet during the late 17th and 18th Centuries, were taken directly from the not-so-secret romantic ‘Language of the Fan’. This codified practice involving the fan was used by young ladies to communicate with their suitors when under the watchful guard of their chaperones. With theatre forever serving as the mirror of contemporary society would emulate this on stage.

Mime continued to flourish in ballets long after when the custom of the mask was finally abandoned by the bastion of Ballet, the Paris Opéra in the 1780s. This was precipitated by Auguste Vestris, who of a famed dancing family, was asked to perform when his father, Gaetano, had become too ill to dance. Auguste agreed only on the proviso that he did so without wearing the obligatory mask so it would be known to the audience that it he who was dancing instead of his famous father. The administrators desperate for the production to be performed agreed and Ballet was changed forever.

By the Romantic era of the 19th Century the majority of the vocabulary contained within had become set in tradition and was only re-interpreted for the new audiences of the day. The early 19th Century was the height of its use and was seen as an essential part of Ballet’s drama; an integral part of any theme or story being played out on the stage with the added ambience of the music to help heighten the experience.

The ballet “Giselle’” (1841) is one particular production that has mime as an integral part of its storytelling, particularly in the first act. The gestures are instrumental to its choreography, that to omit them is to render the poetic qualities of the production impotent. These include those used in the famous prelude to the pas de deux when the young lovers, prince incognito, Albrecht and Giselle, mimic the action of plucking the petals off a daisy. A traditional game of ‘Loves Me, Loves Me Not’ that young lovers are known to play to be followed with Albrecht raising his hand above his head with two index fingers together upright in order to declare an oath of love. Then there’s the gentle rolling of the hands by Giselle as they are raised above her head, to open into a port de bras as to mean, “Let’s Dance”; Berthe, Giselle’s mother, crossing her arms at the wrists inferring impending doom; Hilarion with his hands over his heart expressing his love for Giselle; then there’s Bathilde, Albrecht’s fiancée, pointing to her wedding finger as to signify her betrothal to Albrecht to be later echoed in gesture by him in confirmation thus exposing his betrayal of Giselle which ultimately resulted in the suicide of Giselle. There are myriads of other more subtle gestures in “Giselle” that no wonder it is often referred to as a ‘Ballet-Mime’

The ballet “Giselle’” (1841) is one particular production that has mime as an integral part of its storytelling, particularly in the first act. The gestures are instrumental to its choreography, that to omit them is to render the poetic qualities of the production impotent. These include those used in the famous prelude to the pas de deux when the young lovers, prince incognito, Albrecht and Giselle, mimic the action of plucking the petals off a daisy. A traditional game of ‘Loves Me, Loves Me Not’ that young lovers are known to play to be followed with Albrecht raising his hand above his head with two index fingers together upright in order to declare an oath of love. Then there’s the gentle rolling of the hands by Giselle as they are raised above her head, to open into a port de bras as to mean, “Let’s Dance”; Berthe, Giselle’s mother, crossing her arms at the wrists inferring impending doom; Hilarion with his hands over his heart expressing his love for Giselle; then there’s Bathilde, Albrecht’s fiancée, pointing to her wedding finger as to signify her betrothal to Albrecht to be later echoed in gesture by him in confirmation thus exposing his betrayal of Giselle which ultimately resulted in the suicide of Giselle. There are myriads of other more subtle gestures in “Giselle” that no wonder it is often referred to as a ‘Ballet-Mime’

Unfortunately, this practice would lapse during the 20th Century with it only used when some of the great classics were performed and even then, many versions had them simply omitted. In recent times there have been something of a revival in the use of mime, but on the whole most choreographers tend to regard mime as an obsolete practice that long since passed into history. Therefore, it is only in the great classics of the Romantic era like “Giselle” and “La Sylphide” do these elegant gestures continue to be seen. It is through their practice, we are reminded of the connection and debt that Ballet has to the Commedia.

This article incorporates text derived or information sourced from the following: “Encyclopaedia Britannica” “Commedia Dell’Arte: A Handbook for Troupes”, John Rudin, Olly Crick ISBN: 0415204089, Taylor & Francis Ltd., Routledge, 2001 “The History of Harlequin”, Cyril W. Beaumont, 1926 ISBN: 1906830681, The Noverre Press, 2014 “Mime, Music and Drama on the Eighteenth-Century Stage”, ‘The Ballet d’Action’, Edward Nye ISBN: 978-1-107-00549-5, Cambridge University Press, 2011 “Parisian Music-Hall Ballet, 1871-1913”, Sarah Gutsche-Miller ISBN: 978-1-58046-442-0, University of Rochester, 2015 “The Magic of Dance”, Margot Fonteyn ISBN: 0-563-17645-8, BBC, 1980. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice, Italy Uffizi Gallery Museum, Florence, Italy

Images:Fig. 01– Laura Hidalgo as ‘Titania’ and Rian Thompson as ‘Bottoms’ in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, Queensland Ballet. Photography: David KellyFig. 02– “Nobili in Maschera” (Nobles in Mask) Lithograph of water colour by Giovanni Grevembroch, c. late 18th Century.Fig. 03– Detail of a painting, “La Moretta” by Felice Boscaratti, c. late 18th Century.Fig. 04– Stock image of a contemporary ‘Volto’ mask.Fig. 05– Detail of painting, “Carnival in Venice” by Felice Boscaratti, c. late 18th Century.Fig. 06– Illustration of mime action for ‘Let’s Dance’.

Back To Top

by Adrian Clarke, L.O.C.A.D. – Library of Costume and Design

Imagine if fashion determined a whole new dance style? Well, this is how Ballet began and how the many of the basic steps performed as part of everyday class by dancers were born. Not purely from the pursuit of physical or artistic expression but also from the practical necessity of moving elegantly and practically. From wearing those marvellous creations of Court Dress was born Ballet’s love of the turnout.

From the various ‘Court Dances’ of the latter half of the 15th Century came the earliest vocabulary of steps. These ‘steps’ in turn would form the building blocks for future more elaborate court dances and court ballets with the vocabulary continued to be expanded upon. Meanwhile at the heart, was the symbiotic relationship between Dress and Dance only to become further intertwined as time progressed. Sometimes as such it was unclear which was the greater in the influence.

The grand balls at the Italian and French Courts were particularly rich fertile grounds for the ‘Art of Dance’. This was expedited by how the court dances not only increased in variety, but also in the complexities of how they were to be performed. So ‘Dancing’ became no easy ‘Accomplishment’ for any enthusiastic courtier. This would have courtiers with the means to employ ‘Dance Tutors’ for themselves, and their children, ensuring that they were kept up to date with the latest dances and techniques.

Fig. 01

We get an idea of this from the few tutors who would attempt to document the ‘Art of Dance’. One of the earliest of these would be by an Italian dance master by the name of Domenico da Piacenza (Dominic from Piacenza). Dated circa 1455, it is surmised he wrote his eloquently written “De arte saltandi et choreas ducendi” (On the Art of Dancing and Choreography) at the height of his career as dance master at one of the Courts of the ruling d’Este family in Ferrara. Within this manual of 21 chapters, he summarised in exacting detail various court dances with many of them of his own choreographic composition accompanied by his own music supported with a list of twelve basic steps complete with definition and description of technique. It also included such aspects about timing and “contra tempo”.

One of Domenico’s noted pupils, Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro (William Hebrew from Pesaro; the term ‘Hebrew’ is in reference to his Jewish heritage) also wrote a manual on the subject matter. His intricately illustrated “De pratica seu arte tripudii vulgare opusculum” (On the practice or the art of dancing) was an undertaking that took the diligent pupil thirty years to complete with its publication in 1463. He presented it to Galeazzo Maria Sforza who would later become the Duke of Milan in 1466. Sometime after this, Guglielmo would become a Christian and his godparents would be none other than their graces, Duke and Duchess of Milan themselves. He would then go on to write another treatise under his Christian name of Giovanni Ambrosio. In all his writings he would write in reverential regard of his teacher and dance master, Domenico da Piacenza, often describing himself as a humble imitator.

The other noted pupil of Domenico was Antonio Cornazano, a humanist and poet. He was the author of a fourth important treatise, “Libro sull’arte della danzare” (Book on the Art of Dancing) included 11 dances by Domenico da Piacenza and three tenor melodies for the ‘Bassa Danza’. It was presented as a gift to the daughter of the Duke of Milan, Ippolita Maria Sforza, upon her marriage to Alfonso, the Duke of Calabria in 1465, who later would become King Alfonso II of Naples.

The interesting thing about these named books is their titles. The first two are in Latin. Remember that in Latin there are specific terms for various forms of Dance. Domenico use of the verb is from ‘Saltare’ which is a secular notion of dance but it is still referred in conjunction with the idea of it as an ‘Art’. Guglielmo, however, uses the Latin verb, ‘Tripudiare’ which is a notion of a religious rite but this is compromised by the added use of ‘Vulgare’, obvious meaning ‘vulgar’ as if it was a profane act as oppose to a spiritual one. Was he inferring that there was something ‘devilish’ in dance? Yet in the book, he writes of dance and his dance master with reverence and due respect of the ‘Art’. However, the third named book by Cornazano is in the Italian of the day. He writes of the art in a more matter of fact manner making it readily accessible to the reader in the common language of his native Italy using the Italian verb, ‘Danzare’. What makes this the more intriguing; none of them uses the verb ‘Ballere’ which both terms of ‘Ball’ and ‘Ballet’ are derived. Clearly for these masters, dancing was strictly in the realm of the ‘Art of the Social Graces’ not a theatrical one. The notion of Dance as a performance art would develop sometime later, and particularly in the city of Milan due to the patronage of the ruling family, the Sforzas.

In spite of the slight differing takes on Dance, these particularly mentioned dance books would serve as models for all future ‘dance manuals’. Many of these would vary according to where they were developed in the description of technique and use of terms. Although with the exchange of ideas and techniques among the travelling dance masters from various European Courts would further the cause in such writings. They recognised the need for Dance to be documented and understood as an intellectual pursuit as well as physical one. Therefore slowly over time, an eventual common form of ‘Dance Technique’ would develop thus enabling an even more rapid dissemination of Dance as an ‘Art’ throughout Italy and Western Europe. The popularity of such manuals be it on the subject of dancing or a myriad other subjects such as art, music, philosophy would come to form the basis in the education of the elite during much of the Renaissance era. However in regards to Dance, a universal documented form of technique complete with a specified notation wasn’t realised until the late 17th Century in spite of earlier attempts.

Many of these manuals would describe Dance as an experience of noble pursuit and viewed as integral to the nature of a greater whole personified in the ‘Civilise Being’ along with the trappings of elegant attire. Some would even devote some text describing how best to be dressed for the experience and how dress must enhance the posture and carriage of the body. The illustrations in these manuals helped further the idea of how one must appear similar to how many modern day lifestyle magazines do today.

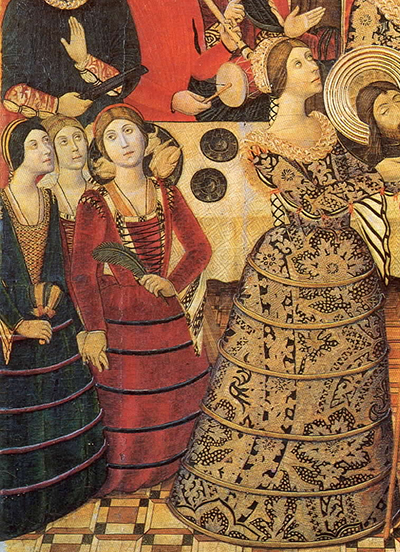

With all this, clearly gives evidence that ‘Court Dress’ had great impetus into the technique required for the practice of ‘Court Dance’. This perhaps is worth to reiterate the description of the basic execution of the ‘Tendu’. As previously explained, it was a movement developed particularly for ladies at court with their long skirts and later the hooped ‘Spanish’ farthingales, as pictured. What seemed to be a simple action of stepping forward was sometimes wrought with a degree of danger in tripping on the skirt’s hem or the bottom most hoop of the farthingale. The idea behind the ‘tendu’ was to lift the hem or hoop clear of the foot just by maintaining continued contact with the floor by sliding the foot forward, extending the leg with it finally only touching the floor with its toes when the foot was pointed. By doing so this ensured the lady of an elegant means of stepping forward without the embarrassment of falling flat on one’s face in the presence of her most Royal Host and other courtiers.

With all this, clearly gives evidence that ‘Court Dress’ had great impetus into the technique required for the practice of ‘Court Dance’. This perhaps is worth to reiterate the description of the basic execution of the ‘Tendu’. As previously explained, it was a movement developed particularly for ladies at court with their long skirts and later the hooped ‘Spanish’ farthingales, as pictured. What seemed to be a simple action of stepping forward was sometimes wrought with a degree of danger in tripping on the skirt’s hem or the bottom most hoop of the farthingale. The idea behind the ‘tendu’ was to lift the hem or hoop clear of the foot just by maintaining continued contact with the floor by sliding the foot forward, extending the leg with it finally only touching the floor with its toes when the foot was pointed. By doing so this ensured the lady of an elegant means of stepping forward without the embarrassment of falling flat on one’s face in the presence of her most Royal Host and other courtiers.

As the century wore on entering the 16th Century, the demand of technique would only intensify in order to accommodate new fashion trends. Furthermore, the new dance spectacles of the ‘Balletti’ were beginning to be seen at many European courts adding further demands in tecnique.

This brings us now to another particular Italian dance master, Cesare Negri, for some unknown reason was called “The Trombone”, who would later come to prominence. Born in Milan, 1536, there are several documented accounts of his exploits as he was well travelled and appeared at the many grand courts of Europe. As a Milanese, he clearly embraced the various established performance traditions of Milan, especially that of the ‘Spectaculi’. How could he not for Milan was very much at the forefront in such pursuits of the Arts, particularly that of Dance.

Negri’s reputation would increase as did his status in becoming something of a celebrity by way of a famed dancing virtuoso and choreographer within the exclusive world of courtiers. Furthermore, wherever, he was very demanding of whoever he taught regardless of their status. This was often to their ire but they endured his ego for he was the ‘Maestro’. This had to do with his very exacting views of how each step was to be performed complete in the manner of carriage and dress. This included how the feet were positioned and ‘turned out’ liken to modern day techniques. He had them performing almost to the same level we expect of professional dancers mastering ten different kinds of pirouettes. This perhaps explains the reason behind his nickname along with his reputation for name dropping, meaning, “Blowing One’s Horn”.

The reason behind for bringing attention to the exploits of Negri and his contemporaries is due to their efforts in raising the status of Dance as a profession as well as an art. Through them, Dance became more than a series of elegant poses and steps up and down the grand halls. It now had names of dances that gave clear references to specific complex choreographies. The development of a vocabulary of terms that would became a whole new language of Dance.

Fig. 03

Negri had very strong opinions in regards to the qualities of dance and was not afraid to express them. This was of course included all aspects of how one was dressed for the practise. This perhaps can help explain his obsession with the turn out. Its use complimented the aesthetic of the human form even though it was not natural to it. By turning out the leg from the hip enabled the muscular line of the male legs to be better appreciated which most body builders today well understand. Furthermore, this also helps make one appreciate the vanity behind the use of tights as 16th and 17th Males were obsessed with the size of their calves. This would only help drive the creation of poses that best achieve this display of ‘Maleness’.

Negri had very strong opinions in regards to the qualities of dance and was not afraid to express them. This was of course included all aspects of how one was dressed for the practise. This perhaps can help explain his obsession with the turn out. Its use complimented the aesthetic of the human form even though it was not natural to it. By turning out the leg from the hip enabled the muscular line of the male legs to be better appreciated which most body builders today well understand. Furthermore, this also helps make one appreciate the vanity behind the use of tights as 16th and 17th Males were obsessed with the size of their calves. This would only help drive the creation of poses that best achieve this display of ‘Maleness’.

Negri is attributed with the earliest attempt in the establishment of the positions of the feet. There appear to have been five positions but some of his contemporaries would subtract or add to these. For example, what we know as 3rd and 5th positions would be taught by some as the one and the same. The amount of ‘crossover’ was at the discretion of the dancer and more the crossover was a measure of the dancer’s ability. Others would rearrange and create new positions, combining parallel and perpendicular positions increasing the number of positions to seven or eight. The debate surrounding what were the positions of the feet would continue for some time.

Regardless, thanks to the likes of Cesare Negri, Fabritio Caroso and Pompeo Diobono the basic notion of dance as a profession has been achieved though be it by the gracious consent of their masters. All of these Italian dance masters found their way to the French Court and brought with them the already established Milanese tradition of court entertainment. Following in their footsteps was none other Baltazarini de Belgioioso with a group of violinists invited by the French Marshal in 1555. Belgioioso, a competent dancer as well as a violinist, would gain favour from Catherine de Médicis and would remain at the French Court. Beaujoyeulx, as he later became known in France, would absorb the Milanese tradition with the theories espoused by the Académie de Musique et Poésie (Academy of Music and Poetry) established in 1570 by permission of King Charles IX with encouraged support from Catherine, the Dowager Queen. These theories aimed to combine music, verse and dance as part of a greater artistic expression, including aspects of social manners and etiquette. This was essential in regards what to come a few years later from Beaujoyeulx with his greatest singular achievement in the first true ballet, “Le Balet Comique de la Royne” (The Queen’s Comic Dance) in 1581. All this was made possible with elements in Court Dance, performance skills from the Commedia dell’Arte and the steady flow of new techniques from Italy.

The first attempt of clarification of these along with other aspects was a book written as a historical retrospective on Dance by a French priest, Thoinot Arbeau, called, “Orchésographie” in 1588 but published in the following year. The book was written as liken to a script, a conversation between an aging Dance Master and a student. It outline detailed principles that would form the basis of the five fundamental positions of the feet for Dance and ultimately for Classical Ballet.

Negri would also go on to write a dance book himself in 1602 called “Le Gratie d’Amore” (The Graces of Love) and would be reprinted in 1604. The term ‘Graces’, is to infer a connection to the three deities from Classical Greek mythology. There were many sculptures and paintings depicting the ‘Graces’ with one of the most famous being in the painting, “Primavera” (Spring) by Sandro Boticelli in c. 1482, as pictured. Each represented a quality that was attributed to any human pursuit, particularly to that of music and dance. They were mostly known as Aglaia (Splendour), Euphrosyne (Joy) and Thalia (Gaiety or Festivity). This was a clear reference to the notion of how Dance was espoused as a means of artistic expression and a total experience for mind, body and soul. So following this train of thought, one could have the title translated as “For the Love of the Graces”.

Negri would also go on to write a dance book himself in 1602 called “Le Gratie d’Amore” (The Graces of Love) and would be reprinted in 1604. The term ‘Graces’, is to infer a connection to the three deities from Classical Greek mythology. There were many sculptures and paintings depicting the ‘Graces’ with one of the most famous being in the painting, “Primavera” (Spring) by Sandro Boticelli in c. 1482, as pictured. Each represented a quality that was attributed to any human pursuit, particularly to that of music and dance. They were mostly known as Aglaia (Splendour), Euphrosyne (Joy) and Thalia (Gaiety or Festivity). This was a clear reference to the notion of how Dance was espoused as a means of artistic expression and a total experience for mind, body and soul. So following this train of thought, one could have the title translated as “For the Love of the Graces”.

The point is that it was from the formality of Negri’s technique and his contemporaries would have dance through their efforts come with a degree of expectations and a level of commitment that evoked a sense of vocation, a profession; a shift in attitudes. For the likes of Arbeau, Beauchamp, Feuillet, Rameau could not have developed their enduring influential works if wasn’t for Negri. Furthermore, nor Beaujoyeulx could have created the ‘First Ballet’. Negri was instrumental.

How is all this relevant to Ballet? Answer is everything and nothing. The paradox lies with an inevitable shift, well more of a redefinition of Dance at the French Court by way of establishment of differing levels in its pursuit. This did have a lot to do with how it was performed, by whom, and the nature of its performance, predominantly either as ‘Court Dance’ or ‘Court Entertainment’. This did come as a breath of fresh air for the professional dancers. Finally they would begin to have an input into how they were dressed. This was a direct result of the rise of Ballet as a performance art thanks to Catherine de Médicis and later to the future Bourbon Kings of France. However, ‘Court Dress’ wasn’t going to let go of its grip on Dance that readily, well not yet.

‘Court Dance’, however, continued to be compelled to accommodate the new fashion trends. These by the late 1500s would include the high necked collars called, “Ruffs” with their ever expanding circumference accompanied by billowing sleeves. Men wore “Trunk Hosen”, balloon like shorts. There was the new ‘French or Cartwheel Farthingale’ with its expanded dimension liken to a wagon wheel laid horizontal around the ladies’ waist. These fashion elements would render placing of the arms at the sides impossible. So it was required to arrange their arms in a variety of elegant positions. This resulted in one of the most lasting traditions of Ballet technique. It is what is known as the ‘Carriage or Breathing of the Arms’, or in ballet terms, “Port de Bras”.

It is pertinent to draw attention to the rigid fit of ‘Court Dress’ for both Lords and Ladies alike. It limited movement of the arms and the manner how the torso was held. The corset now had the ladies particularly in rigid poise. For the gentlemen wore a rigidly padded ‘Doublets’ often with a small pronounce belly like protrusion called a “peascod”. It too had the lords always appearing in an upright stance. The relaxed curvature of the torso was not to be tolerated. The chest or bossom was to protrude overtly with shoulders back as if a peacock. This manner of carriage was well demonstrated in the court dance of the ‘Pavane’. This slow formal dance was specifically created for this purpose as inferred by the meaning behind the word was this named bird of paradise. Danced to a timely measure, they ‘strutted’ their stuff with all the elegant arrogance and conceit one could muster. The ‘Pavane’ is a perfect example of this marriage between Dance and Dress. It was all about the precision of execution in technique, presentation in dress complete with an air of perceived nobility that was deemed necessary in the achievement of an ‘Accomplished Civilise Being’.

Following 1581, you would be forgiven to think with Ballet acquiring its status as a performance art that ‘Dance’ and ‘Dress’ would go their separate ways. Well sorry to disappoint, it didn’t happen. At the French Court, Ballet would continue to be performed by members of the Royal Family, the Nobility alongside professional artists. Therefore, it was still bound by the conventions surrounding the French Court and when at Court you were expected to follow them. In fact, the convention of Court Dress would remain as a dominant influence well into the 18th Century. This imposed bond to ‘Dress’ can be understood by how artists employed at Court were listed as part of the ‘Écurie’, which literally means ‘Stable’. This does make one view the ‘Pas de Cheval’ (Horse Step) in a new light.

Costume wise, what happened was intriguing. A particular type of costume was developed and it was specifically created for Ballet but it was only worn by male dancers. It appeared at the turn of the 17th Century and would develop and become very much entrenched as part of Ballet over the course of the next 150 years. This is what would become known as the ‘Tonnelet’, a name that takes delight in its epicurial connection to fine dining at lavish banquets where ballets were regular performed as part of Court Entertainment. Its story is another one and best to save for a future edition.

As the 17th Century progressed, gowns would be made in lighter fabrics such as the new silks imported from India and other parts of the Orient. The ruffs were to disappear in favour of wider necklines and flatter collar styles with sleeves to lose their size, often more fitting or falling into folds and small puffs. More importantly, the familiar Farthingales would also lose favour giving way to layered petticoats. This new style however did cause a new set of challenges for the ladies. As there was no hoops holding the skirts away from the legs this did have swathes of fabric falling into the legs when moving. This would make walking difficult, let alone dancing. Despite various techniques employed by dressmakers in the construction of the skirts and petticoats which did help, but the problem persisted. This did have many ladies resort to the unflattering practice of the ‘petti kick’ to ensure that they wouldn’t be tripped over by their petticoats. What made this situation worst was that many would have their gowns furnished with a train as it was the rising vogue. With more length in the skirt at the back did bring more added concerns for the wearer. Now with the new livelier dances combined with the new vogue it was evident new dance techniques and dress codes were needed.

Although the practice of the technique of keeping continued contact with the floor known as “à terre” was well established by the 17th Century. This was also true in the use of the turn out as well, be it not at the degree of today. What would transpire though from the known practises would only further be expanded into an evolving vocabulary of movements for Dance and Ballet.

For example, the ‘petti kick’ would become the ‘glissé’ meaning ‘to slip or slide’, this was in reference to have the foot slip or slide out from under the hems of the petticoats.

Then there was the ‘turn out’ which was essentially developed to help pander to the male ego, would help in the development of a more elegant technique for ladies as well. When walking in the more natural parallel manner it was discovered how the legs would quickly be enveloped in the volume of fabric in the layers of petticoats. This was even more noticeable when one would try and lift a leg. What would develop is a stylised walk that many dancers perform today now known as “la promenade” as to infer an elegant walk, originally it was “la marche du cygne” (the swan walk). The purpose of the swan walk was two-fold, to clear the way and a means of stepping forward or sideways. In a way it was a reinvention of the ‘tendu’. This was achieved by maintaining a turn out from the hip, raise one foot by bending the leg until the sole of the foot is parallel to the supporting leg at the ankle with foot pointed and the toe of the shoe touching the floor. By doing this help to lift the weight of the layers away from the pointed foot. While maintaining contact with the floor or just off with the leg still turned out unfold the leg in the desired direction with the foot pointed; then step by placing the foot down bringing the heel forward ensuring the continued turn out of the leg when transferring the centre of weight from the supporting leg; when have completed the step, have the other leg brought in ready in the same position of bended knee and raised heel at ankle ready for the next step. Male courtiers would later adopt this technique following the introduction of the long jackets of the late 17th Century.

Another was the awkward swish that helped clear the falling layers around the ankles became the ‘ronde de jambe’ (rounding of the leg) ensuring clearance for an elegant means of stepping in the desired direction.

Then there was the ‘En Cloche’ (Bell like) move. As per most Medieval and Renaissance court dances, the body was expected to be always kept upright. However, many of the new dances required legs to be lifted often to the shocking height of a 45 degree angle. This was difficult due to the rigidity of court dress particularly for ladies with their corsets and the layers of petticoats under their skirts. However by a gentle tilt of the body in the opposite direction to the raised leg, this was achievable.

It was about this time the earliest examples of a ‘Ball Gown’ were to appear as a result of these new dances needing to be accommodated. For noblewomen this would have ‘Court Dress’ evolve into three distinct gowns, Robe de Cour (Court Dress) for the daily appearances at Court; Robe de Bal (Ball Gown) specifically for purpose of dancing at a Ball at Court; Robe d’État (State Dress) for ceremonial occasions at Court such as the presentation of the Monarch after Coronation or the start of the season at the French Court.

Fig. 05

These distinctions were inevitable as the idea of performing a court dance in a gown furnished with a train did proved difficult for most. In saying that, there were occasions that it was expected to do just that thus giving rise to the term of ‘arrondir’ which means ‘the rounding of’, the term is still in use in Ballet today, but more to do with the arms. The use of ‘arrondir’ in this case is specific to the ‘Promenade’, a particular Court Dance was only performed for very grand ceremonial occasions; an already some centuries old tradition of the French Court by the 17th Century.

These distinctions were inevitable as the idea of performing a court dance in a gown furnished with a train did proved difficult for most. In saying that, there were occasions that it was expected to do just that thus giving rise to the term of ‘arrondir’ which means ‘the rounding of’, the term is still in use in Ballet today, but more to do with the arms. The use of ‘arrondir’ in this case is specific to the ‘Promenade’, a particular Court Dance was only performed for very grand ceremonial occasions; an already some centuries old tradition of the French Court by the 17th Century.

In essence, it was a ritualistic choreographed procession, an ostentatious display of aristocratic splendour commonly known as the ‘Pageant of the Peers or Nobles’. Young noble ladies presented at Court for the first time also performed in a promenade usually at the start of the season. Over the course of the latter half of the 17th Century, these ‘Promenades’ would only become grander and the trains longer.

To be successful in execution of the ‘arrondir’ in this sense was to be sure that the train was trailing behind at all times, particularly when it was required to return to where one has come from as simply stepping backwards clearly wasn’t an option. When performing the ‘Promenade’ positioning was everything, namely always forward of the train. The notion of ‘rounding’ was as if in a circle, with her escort had to be sure he was always on the inside of his companion. So if turning left, he was to be at her left and vice versa if turning right. Otherwise, he would be forever getting in the way. The ‘arrondir’ is similar to the equestrian practice of ‘Longeing’ or ‘Lungeing’ where a horse is asked to perform going round in circles at the end of a long line, responding to commands from a handler on the ground at the circle’s centre holding the other end of the line. So in this context the lady is the horse and is guided by the hand of her escort always going around him in a forward motion. If a lady was to turn on her own, she must do so in a circular motion with the end of the train at the centre of the circle ensuring that she would not be entangled. This technique was also used when wearing long capes as it was the case in many early ballets along with the countless processions and carousels. Furthermore, most ballets today tend to have the male dancers on inside of their female counterparts when performing in circular formations, an evident influence from the ‘arrondir’.

In 1654, when a young man of the age 15 years was crowned as King Louis XIV, little did the French courtiers know what was installed for them. As a political ploy, he would commission new court dances to be choreographed. Not just for his coronation but regularly, often to the distress of his courtiers who were expected to keep up with the latest dance moves. This would also create a new aesthetic in the performance and presentation of dance culminating in what would become known as the “Noble Danse” (Noble Dance). This was a creation born from Louis’ developing vision for France and the manner of his Court. Following the death of his First Consul, Cardinal Mazarin, now 22, Louis would exercise his divine right as the absolute authority and have the French Court totally restructured ensuring that he was at its centre. He had the Court re-dressed in a new fashion reflecting its new found modernity. In the same year, he established the Académie Royale de Danse (Royal Academy of Dance). He loved dancing himself. Under Louis, all that had preceded him combined with the new dances he had created, Dance would reach a pinnacle never before seen and not since replicated.

This new aesthetic was reflective of a developing artistic expression arising predominantly within the visual arts and architecture. Louis would grow with this artistic movement nurturing it to full flowering beauty. This was of course the ‘Baroque’ era. The time of Louis’ reign (1643 – crowned 1654 – 1715) would serve as the period of transition from the remnants of Renaissance ‘Mannerism’ to the Baroque ‘Flourishes’ but it was also one of a stark contrast between his political will and his intellectual and artistic pursuits. Regardless of this paradox, the Baroque style was important to French Ballet in ways that will need to be explained another day. However, this was also important to the ‘Noble Danse’, particularly musically. The complexities of the new dances correlate directly with the new musical style of this era which for music began as early as the 1580s. Because of this, Louis would seek means to have this formalised and made clear for his own sake as well as for all within the French Court. This would help explain why Louis would establish the Académie Royale de Danse for this very purpose with the hope of furthering the cause for creating a clear definitive approach in dance according to his vision of the art.

Fig. 06

Sometime not long after this, Louis would appoint Pierre Beauchamp to create a system of teaching and cataloguing of the various court dances, particularly those of the new ‘Noble Danse’. The idea was to ensure that it was Louis’ vision for dance was to spread and serve as the basis of dance instruction within and out of the French Court. Starting with the myriad of steps known to exist at the time and all previous documentation, Beauchamp achieved this by stripping back the layers of tradition that had evolved over the near two centuries. He identified them in accordance to their perceived origins and technique, sometimes according to their engendered use.

Sometime not long after this, Louis would appoint Pierre Beauchamp to create a system of teaching and cataloguing of the various court dances, particularly those of the new ‘Noble Danse’. The idea was to ensure that it was Louis’ vision for dance was to spread and serve as the basis of dance instruction within and out of the French Court. Starting with the myriad of steps known to exist at the time and all previous documentation, Beauchamp achieved this by stripping back the layers of tradition that had evolved over the near two centuries. He identified them in accordance to their perceived origins and technique, sometimes according to their engendered use.

After he compiled all he could, he would then develop a new form of notation to document all these steps giving them their own specific symbolic reference liken to the notes of a music manuscript. Beauchamp’s notation created a new means of dissemination in a new language of French Dance. However it was never published, it was only ever used by his pupils within the confines of the Royal Academy of Dance and later at the Académie Royale de Musique (Royal Academy of Music), otherwise known as the Paris Opéra.

It would be one of his pupils, Raoul Feuillet, who would author of one of the earliest publication of dance notation based on the Beauchamp system. Not only did it spread within France but beyond its borders across Europe like wild fire. By default, this would usurpe Italy’s influence and put France at the centre of European dance culture with Louis XIV at the very heart of it.

The influence of these books would continue for many decades following with their various translations. The Beauchamp-Feuillet system would be reviewed by Pierre Rameau in 1725. This publication most dance history buffs are familiar with. All this was made possible by what Beauchamp produced and it was imperative to the foundation of Ballet as we know it today. At its core, what we know as the ‘Five Positions of the Feet’. The manner of their placement clearly demonstrates the influence of dress had across the generations of those artists, courtiers and dance masters before him who danced in the great halls of the French Court.

So when practising, look into the mirror and just try to imagine what it was like way back when in the hope giving greater inspiration and motivation behind those beautiful tendus and port de bras.

This article incorporates text derived or information sourced from the following: “Encyclopaedia Britannica” “Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani” “Fifteenth-Century Dance and Music” Volume One: Treatises and Music, A. William Smith ISBN: 0945193254, Pendragon Press, 1995 “The Dancing Master”, Pierre Rameau Translation: Cyril W. Beaumont, 1931 ISBN: 1852730927, Dance Books Ltd., 2003 “DE PRATICA SEU ARTE TRIPUDII: On the Practice or Art of Dancing”, Guglielmo Ebreo Edited/ Translation: Barbara Sparti, Michael Sullivan (Translation) ISBN: 0198165749, Clarendon Press, 1995 “The Violin and Viola: History, Structure, Techniques”, Sheila M. Nelson ISBN: 0486428532, Dover Publications, 2003 “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, Selma Jeanne Cohen and Dance Perspectives Foundation DOI: 10.1093/acref/9780195173697.001.0001, Oxford University Press, Online Pub. 2005 “Le Gratie d’Amore 1602 by Cesare Negri: Translation and Commentary” Translation: Gustavia Yvonne Kendall, PhD Thesis, 2 volumes, Stanford University, 1985 “Dance, Spectacle, and the Body Politick: 1250-1750”, edited: Jennifer Nevile ISBN: 978-0-253-21985-5, Indiana University Press, 2008 “The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet”, Horst Koegler ISBN: 0193113309, Oxford University Press; 2nd Edition, 14 October, 1982. “The Magic of Dance”, Margot Fonteyn ISBN: 0-563-17645-8, BBC, 1980. National Library of Australia, Canberra Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand Library of Congress, Washington D.C., United States

Images:Fig. 01– “Cassone Adimari”, by Scheggia (Splinter), Galleria dell'Accademia, Firenze, Italy.Fig. 02– Detail from the painting, “Retable of St. John the Baptist” by.Pedro García de Benabarre c.1480. Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain.Fig. 03– Portrait plate of Cesare Negri from, “Le Gratie d’Amore” by Cesare Negri, reprint 1604.Fig. 04– Detail from the painting, “Primavera” (Spring) by Sandro Boticelli, c. 1482. The Ufizzi Gallery Museum, Florence, Italy.Fig. 05– Lithograph of French Baroque Court Ladies by Henrick Keller. Frankfurt, Germany. 1889.Fig. 06– Detail from a Plate, “The Art of Dancing Explained”, by Kellom Tomlinson, London, England, 1735.Fig. 07– Plates of the Five Positions of the Feet from “Le Maître à Danser” by Pierre Rameau, 1725

Back To Top

by Adrian Clarke, L.O.C.A.D. – Library of Costume and Design

Let us embark on a journey through the history of Ballet but not how it was danced but how it was dressed. Why? It is important to understand that Ballet has evolved in symbiosis with its costumes over the course of the past five centuries. The impact of ‘Costume’ on ‘Dance’ and vice versa has been both intriguing and beguiling. From it came a combination of the many aspects including social convention, practicality and the prevailing aesthetics of the day. Ballet would evolve and continues to do so in a way rendering it unique among the performance arts.

In order to begin this journey, one must first understand the culture of the day all those centuries ago in Europe at the time of its birth. As already explained previously, Ballet was born from two worlds. It is the world of the Royals and nobles that is the focus of this article. It was in the opulent surroundings within the Grand Palaces the very notion of Ballet would be realised. Ballet would come to embody the very idea of a ‘Cultured, Civilise Noble Being’. This was an ideal developing out from the new social awakening of the ‘Renaissance Era’ that would envelope Western Europe for two centuries. During this ‘Flowering of Learning’ was revived the many ancient Greek and Roman teachings regarding ‘Humanity and Civilisation’. This would give rise to the notion what we know as the ‘Renaissance Man’.

During the Renaissance there was emphasis on the idea of knowledge, refinement and presence. This would have those of the ruling classes endeavour to demonstrate their physical and intellectual prowess across a wide spectrum of pursuits. This was in order to achieve that enviable title of being called, “Accomplished”. Leonardo da Vinci would later be hailed as a ‘Renaissance Man’ as he demonstrated proficient talents and knowledge in Philosophy, Science, Painting, Astronomy, Engineering, Architecture and Human Anatomy. It is obvious with such a diverse list of interests many of the nobility would hesitate even attempting. Therefore, it was for most courtiers to be considered ‘Accomplished’ the list of requirements was less demanding. Therefore, the general standard was to demonstrate the intellect and the ability to engage in conversation of noted worth. This would include topics such as poetry and philosophy.

There was the added advantage of being able to speak Latin or Ancient Greek as these were regarded as the languages of the ‘Enlightened’ with most books and writings published in Latin.

This emanated from how the Catholic Church once was the single greatest patron of ‘Learning’ with it establishing many universities across Europe. So the eventual use of Latin as a sort of international language of learning was inevitable as Latin was also the language of the Church.

As if to vaguely quote the character ‘Caroline Bingley’ from Jane Austen’s, “Pride and Prejudice”, “No one can be really esteemed ‘Accomplished’ who does not greatly surpass what is usually met with. One must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word; and besides all this, One must possess a certain something in the air and manner of walking, the tone of one’s voice, one’s address and expressions, or the word will be but half-deserved.” Even though this was expressed by Miss Bingley in context of a woman in the Regency period of the early 19th Century; this notion was very applicable to both sexes and certainly to the ‘Renaissance Man’ of the 16th Century. After all, the idea of an accomplished person as espoused by Miss Bingley was first from him.

One may ask what about the ‘Renaissance Woman’? Well, one must bear in mind 16th Century society was still very much patriarchal with men at the centre of all political and social concerns. It was true women were expected to be able to perform the same social graces, but only to the point as a complement of her so called superior male counterpart. If a woman demonstrated too much intellect, it was surmised she would make a poor obedient wife. Elements of this can be appreciated in Shakespeare’s “Taming of the Shrew”, a play about the antics of a scheming hopeful husband out to woo and tame a spirited lady. So it was viewed the woman best kept to contend with safe pursuits such as poetry, music and dancing, leaving the more meaningful pursuits to her lord and master.

This attitude was further exemplified in the early ballets as the focus was on the men as heroic figures. Women were presented in many of these ballets primarily as ‘living props’. Like the magic acts of old when the beautiful lady assistant stood to one side striking elegant poses. Her sinewy arms outstretched drawing attention to the centre where the male magician was performing all the feats of wonder and amazement looking on as if saying, “Oh! He is wonderful, is he not?”

Well? How times have changed …

In regards to achieving one’s manly carriage during the 16th Century, it was generally through the demonstration of one’s physical skills. This would have many pursue fencing and dressage, a refined form of horse riding. Mostly though would indulge in the practice of the ‘Court Dance’.

Meanwhile, not only was one expected to be proficient complete with an air of elegant and felicitous demeanour, but also must appear ‘Fashionably Attired’ in the execution. Therefore, one must present oneself in a befitting style of dress during any of the acceptable intellectual and physical pursuits.

Fig. 01

As a result, this would have many such ‘Renaissance Men’ commission portraits of themselves with symbolic depictions of their ‘accomplishments’. These portraits always presented them fashionably attired while in an elegant, relaxed stance demonstrating their ease among the trappings of noble pursuits. Other portraits would have them simply poised in a demeanour of self-assuredness as if ready to engage in conversation or in a state of wonder, pondering upon the meaning of life to be seen holding a feather quill, a book or human skull or even with all three! Is anyone up for “Hamlet”?

As a result, this would have many such ‘Renaissance Men’ commission portraits of themselves with symbolic depictions of their ‘accomplishments’. These portraits always presented them fashionably attired while in an elegant, relaxed stance demonstrating their ease among the trappings of noble pursuits. Other portraits would have them simply poised in a demeanour of self-assuredness as if ready to engage in conversation or in a state of wonder, pondering upon the meaning of life to be seen holding a feather quill, a book or human skull or even with all three! Is anyone up for “Hamlet”?

This is when clothing, or costuming for that matter, is a perfect example of a tangible manifestation of such abstract notions. As always ‘Need is the Mother of Invention’ and all clothing is born from all sorts of needs. These ranging from the basic like protection from the elements to more abstract notions of cultural and religious identity. For example, when it is cold the norm is to wear a woollen jacket or knitted jumper. Or how do we know an officer of the law? It is from the uniform worn and from which we identify with it a notion of service, protection and safety. So with afore mentioned ideals attributed to an ‘Accomplished Courtier’ they would also come to be endowed in the various costuming traditions that would later be extrapolated into Ballet but Why?

This perhaps can be best understood by taking a step back. First, we need to understand the meaning behind the term of “Ballet” itself. It is an intriguing one as it is a singular term used to describe a collection of dances bound together by a theme or drama. The way this notion developed during the 16th Century, would culminate at the height of the ‘Renaissance’ era.

The word is a derivative from the Latin verb, ‘Ballere’ or the Romana Lingua (common Latin tongue) ‘Ballare’, either way both have the meaning of ‘to dance’. This was in the sense as the most formal and refined notion of the pursuit. So to translate the Latin verb, ‘Ballere’, effectively, into English is best described as ‘to dance formally’.

This formal notion of dance is in context as liken to a debutante from the late ‘Victorian Era’ dancing at her ‘Coming Out’ ball. The ball served as the climax for her countless hours of training and practice in demonstrating all the refinement and skill to dance the waltz. This was no ordinary waltz though, for she would be in a fashionable ball gown complete with a train, long gloves, and a coiffure bedecked with ostrich plumes.

This idea of social refinement in dance stems from the ancient Romans who had very clear concepts in regards to dance – Stately affairs “Ballere”, Religious worship in the form of ritual dance “Tripudiare” and Social pursuits as just for the sake of pleasure, “Saltare”. (Yes the word, ‘Salsa’ comes from this). This thinking would translate into Byzantine and Medieval times with the pursuit of dancing in all its forms under the careful watch of religious censor as exacted by the Church. The notion of “Ballere” would be further expanded upon entering the Renaissance era as ‘Dance’ would come to be viewed as the first refinement of any ‘Polished and Civilise Society’. This notion about the virtues of ‘Dance’ with other social graces would continue well into the 20th Century.

This pursuit of refinement would have the Italians give us the “Ballo”, a term also derived from the Latin verb ‘Ballere’. It was towards the close of the 15th Century at a time when the Church was to relax its attitude towards ‘Secular or Theatrical Entertainment’. This grand courtly pursuit of various dances as executed by courtiers complimented the new rising notion of the ‘Renaissance Man’ with its grandeur and exacting formality. The ‘Ballo’ was quickly adopted by the many courts in Western Europe with the word extrapolated into the relative languages such as “Le Bal” in French, “El Baile” in Spanish and “Ball” in English. Over the course of the late 15th and 16th Centuries, these would develop into spectacular, lavish events often lasting for several hours well into the morning of the next day. As these became more common among the European courts, Balls would serve as fertile ground for those wanting to further their skills in the ‘Art of Dance’. Those with the means employed ‘Dance Tutors’ for themselves, and their children, ensuring their ‘Civilise Status’ at Court. Many of these tutors would attempt to commit these dance lessons and the ‘Art of Dance’ to print. The advantage of this saw an eventual common form of ‘Dance Technique’ developed. However, a universal form wasn’t realised until the late 17th Century.

The technique required for ‘Court Dance’ was greatly influenced by the very nature of ‘Court Dress’. This is best understood by the basic execution of the ‘Tendu’. It was a movement developed for ladies in particular, with their long skirts and hooped farthingales. This was because the action of stepping forward was sometimes wrought with a degree of danger in tripping on the skirt’s hem or the bottom most hoop of the farthingale. It was realised just by maintaining continued contact with the floor, sliding the foot forward, extending the leg with it finally only touching the floor with its toes when the foot was pointed. By doing so lifted the hem or hoop clear of the foot. This ensured the Courtier of an elegant means of stepping forward without the embarrassment of falling flat on one’s face in the presence of their most Royal Host. For such an incident would guarantee her exile from Court and was unable to return unless forgiven by means of a Royal pardon.

‘Court Dance’ continued to be influenced by dress simply because it had to accommodate the new fashion trends of the day. These would include the high necked collars called, “Ruffs” with their ever expanding circumference and the billowing sleeves. The hooped ’Farthingale’ would acquire a new expanded dimension that would render placing of arms at the sides impossible for the wearer. So it was required of the ladies to arrange their arms in a variety of elegant positions. This resulted in one of the most lasting traditions of Ballet technique. It is what is known as the ‘Carriage or Breathing of the Arms’, or in ballet terms, “Port de Bras”. It is pertinent to draw attention to the rigid fit of ‘Court Dress’. Due to as such, the raising of the arms was greatly limited. This was often not much higher than shoulder height with further height only achieved by the raising of the lower arms in a right angle bend at the elbows. This was often accompanied by a flourish of the hands from the wrist. This is often called the “Royal Wave”.

‘Court Dance’ continued to be influenced by dress simply because it had to accommodate the new fashion trends of the day. These would include the high necked collars called, “Ruffs” with their ever expanding circumference and the billowing sleeves. The hooped ’Farthingale’ would acquire a new expanded dimension that would render placing of arms at the sides impossible for the wearer. So it was required of the ladies to arrange their arms in a variety of elegant positions. This resulted in one of the most lasting traditions of Ballet technique. It is what is known as the ‘Carriage or Breathing of the Arms’, or in ballet terms, “Port de Bras”. It is pertinent to draw attention to the rigid fit of ‘Court Dress’. Due to as such, the raising of the arms was greatly limited. This was often not much higher than shoulder height with further height only achieved by the raising of the lower arms in a right angle bend at the elbows. This was often accompanied by a flourish of the hands from the wrist. This is often called the “Royal Wave”.

Meanwhile, there was another spectacular form of ‘Court Entertainment’ coming to the fore. Again it was from the Italian peninsula. It was given either the term of, “Balletti” in Italian or “Balleria” from the Latin. Depending when one was born, one can see from memory of basic high school Italian and Latin these terms were coined in the plural form and not the singular. Perhaps it is poignant to point out that the word, “Opera”, is also the Latin plural for “Opus” (Work). The plural use comes from the notion that an ‘Opera’ cannot be an opera if there is only one song to perform, and as for any opera, it must have a series of songs to carry a theme or drama. This was the same for ‘Balletti’, a collective of dance scenes performed as part of a ‘Spectaculi’ (Spectacles).

Note also how ‘High Art’ had its connection to the ‘Enlightened’ by way in the use of Latin terms – ‘Opera’, ‘Balleria’ and ‘Spectaculi’. As these pursuits were once considered ‘Indulgent’ and ‘Profane’. This use of Latin perhaps was also to pacify the Church by keeping with the language of the Sacraments; the earliest connection of Ballet with the notion of the ‘Divine’ which in the centuries to come would become its obsession.

The city of Milan in Italy would particularly become famous for ‘Spectaculi’ due to the patronage of the Arts by Ludovico Sforza, Regent of the Duchy of Milan. One the most famous of these was part of the celebratory events for the marriage of his nephew, Gian Galleazzo Sforza, the Duke of Milan to Isabella of Aragon in 1489. The nature of these spectacles is best liken them to an elaborately staged dinner Cabaret show, perhaps like those seen on the Gold Coast, Queensland near Warner Brothers Studios.